The

CB&Q Depot at Five Points

by William A. Franckey

The Zephyr, Galesburg

It

seems that there will always be great mysteries, The Great Pyramid, The Holy

Grail, The Ark and Amelia Earhart. Galesburg has a mystery; there is no

photographic image of our town’s original railroad depot. True, on the order of

lost knowledge, maybe more people have wondered about what that Custer was

thinking in the final moments of the Little Big Horn battle than why there is

no surviving photograph of Galesburg’s early wooden depot.

A

town’s railroad depot was a point of pride where a community’s activity hustled

to the sound of trains. Trains arrived and departed so people came and went, as

did information. A depot’s telegraph stretched as far as the iron rails did.

The telegraph office linked early American towns with the heartbeat of America

and a prairie town pulsed at the train platform. This made for a place to

people-watch in every sense of the word. Early depots were always front and

center in a railroad’s operation. Passenger depots economically located freight

offices at one end of the building to accommodate commerce and produce. Larger

terminals may have had a separate building for a freight house or freight depot

whereas the main passenger depot would have still served a variety of

functions.

Within the passenger house would have

been passenger waiting rooms, a barber shop, a restaurant, and possibly

sleeping rooms. In addition to a ticket sales, a station agent would be

assigned there and offices for railroad officers whose duties required

immediate access to the concerns of railroading. Galesburg’s original passenger

depot was such a place.

The

depot became the center of attention soon after its construction in 1854. The

structure was an imposing two story wood building with eleven dormers and four

chimneys. The outside was covered with vertical wood board and batten siding.

This was the same depot that Stephen Douglas arrived at on an eastbound train

from Oquawka. Douglas stepped off of his coach on the platform and headed towards

the Bancroft Hotel on his way to debate Abraham Lincoln at Knox College just a

few hundred yards away. The Northern Cross Railroad stretched from Quincy

through Bushnell to Galesburg’s depot with the Central Military Tract reaching

to Mendota. Also, the Peoria and Oquawka crossed at the station platform. All

of this under the control of the Chicago Burlington and Quincy Railroad.

Ownership would be achieved later but control was always at the forefront. The

CB&Q’s small railroad yard was located here with an assortment of railroad

buildings, roundhouses, machine shops and wood and coal chutes for the hungry

steam locomotives. A short distance away stood Galesburg’s freight depot —

practically the same size but with only a single story.

Galesburg

began its railroad heritage with a meeting in the dining room at the farmhouse

of at George Washington Gale Ferris. This is where the idea of constructing a

railroad on the prairie was entertained. Ferris remembered that two or three

meetings were held at the farmhouse. By early January 1851, contracts were

entered into for grading and masonry. A meeting of the incorporators was held

at the Academy, a little building on Galesburg’s Main Street, March 8th, 1851.

Plans and action now would link Galesburg to Chicago and to the west.

William

Whittle, a Civil Engineer, was first charged with railroad construction. Soon,

John M. Berrien became Chief Engineer for Galesburg’s Central Military Tract

Railroad. Berrien is remembered for the fireproof safe he designed in the

CB&Q’s main office in Chicago. During the Great Chicago Fire, Berrien’s

safe proved effective and the railroad’s corporate papers survived intact.

Finally, tracks were laid at Mendota toward Galesburg, connecting the Aurora

Branch Railroad from Aurora to points west. Construction inched across the

prairie and local newspapers reported the progress. Soon a construction train’s

whistle was heard outside of Galesburg. About where the current Amtrak Station

now sits, huge mountains of railroad ties stood and around this area were tents

for the construction workers and track gangs.

Buried

in microfilm is fleeting reference to a platform and possibly a small temporary

structure which served briefly as a depot but was eclipsed by a prominent

two-story wooden passenger house. The first construction train rolled in and

soon the first passenger train linking Galesburg with Chicago. Galesburg was

jubilant at the prospects that a railroad would bring.

Quickly,

this attitude took on a somber tone. Galesburg thought they had gained a

railroad but discovered that the aggressive railroad had instead, gained a

town.

A

look at any city map of Galesburg shows orderly, well laid city blocks but the

railroad had sliced into town at an angle. Clearly there became a “wrong” side

of the tracks with Knox College on one side of the “Q” depot and the noisy and

dirty railroad shops on the other side. To make matters worse, the railroad

brought in immigrant workers and exploited them; the business of railroad work

was a brutal one. Now the little hamlet of Galesburg, whose early focus was

work and religious study, began to see an element of drifters, boomers, tramps

and sluggers from abroad. What Galesburg hoped to develop away from had

followed the town courtesy of the new railroad.

Each

hotel in Galesburg would have two to six men acting as “runners” for the

purposes of solicitation of business. Trains arriving at the depot brought some

passengers who wished to take other trains and consequently had to detrain onto

the platform. Some waited on the platform to board and upon almost every train

were those who wished to get into the passenger house for a meal or other

reasons. In 1857, the proprietor of the Victualing House located within the

depot found the situation so intolerable that he approached railroad

superintendent Hitchcock. Hitchcock added his weight to the situation and an

ordinance was passed limiting the number of runners per hotel. The restriction

applied to the platform but just off company property the ordinance did not

apply. Because of the comings and goings of horse drawn carriages, known as

taxis, trouble remained around the depot.

The

upper floor of the depot had sleeping rooms that were contracted to an

independent business group which operated the Depot Hotel. The other hotel

owners cried foul, that the money generated by Depot Hotel did not stay in

Galesburg but found its way back to Chicago. This was not true but the other

hotels in Galesburg tried to create a boycott of the depot’s hotel thus

increasing their own wealth. This was know early on as the Hotel Wars of

Galesburg.

Abraham

Lincoln was once found on Main Street after having received a haircut and asked

an old acquaintance to walk with him to the depot. Lincoln would then wait for

a train. Also at the depot, was a well known Galesburg personality with the

name of Peanuts. Peanuts was a station boy who worked the depot and platform,

undoubtedly hailing taxis and announcing arrivals and departures of trains.

Stranger yet, the depot was, for a short time, used for religious services on

each Sunday with a different denomination being represented each week.

The

railyards located close to the depot, had a series of tracks where the

railroad’s cabooses, called waycars on the Burlington, were stored. Because of

the increasing amount of taverns, then known as Sample Houses, surrounding the

depot, some inebriated patrons used the waycars as temporary sleeping quarters.

It was said that the nightly commotion in this area reached such a state that

some people living a half mile away from the depot thought the little depot to

be on fire. In front of the depot, five streets came together and of course

this was known as Five Points.

Ed

Morrisey, a local policeman, was assigned to control the mayhem at the “points”

— warrants by day, arrests at night. No photo exists of Policeman Morrisey but

there is reference that he had scars upon scars. Again, if a picture can speak

a thousand words, one can see how a photograph of Officer Morrisey would add so

much to this story.

Galesburg’s

little depot stood witness through good and bad times. A nationwide labor

strike erupted in 1877 which affected Galesburg. The city’s founding fathers

were still alive so civic responsibility was called for by local newspapers.

Some strikers organized large groups to patrol the railroad’s property and keep

it from harm. This had to perplex the railroad management. On July 29,1877 the

railroad received notice that the protection committee would no longer protect

railroad property. The railroad approached Mayor Stewart that the railroad

needed protection so the city of Galesburg added 20 men to the 35 men the

railroad had in place for protection. Soon the strike ended but the suspicious

railroad understood that unrest lingered. Because of practices the railroad

implemented for the next ten years, an ugly, vicious strike exploded in

Galesburg in 1888.

Gala

parties were part of the lore as the depot was obviously a main focus of

Galesburg. During the first week of February 1881, Miss Newman hosted a party

on the occasion of her 20th birthday. The guest list read like a page from

Galesburg Society. The party formed a grand March and enjoyed a festive dance

that lasted till half past ten when an elegant dinner was served. Professor

Ferris furnished the music. Professors Seville and Booth of Monmouth assisted.

The city depot must have felt as neutral ground on that night and not as ground

on the wrong side of the tracks. No one suspected that within a few weeks, the

depot would received a mortal blow.

The

Galesburg depot suffered a minor fire in 1877 but survived intact until a fire

in 1881. Even though Galesburg’s newspaper described the fire as utter

devastation, the depot did somewhat survive. At 4am on a cold morning, March

1st, 1881, the old wooden depot was discovered to be on fire. An alarm was

sounded by the steam whistle at the railroad’s machine shop. The railroad fire

department, Galesburg’ s fire department and volunteers waded through snow

drifts towards the burning depot. In the cold wind and snow, they fought the

fire until the last flames were out. Although the depot and depot hotel

suffered severe damage, the telegraph offices and depot baggage room were

saved. Two railroad coaches were used as a temporary depot until the depot was

repaired in part. The railroad apparently wasted no time in repairing the

structure as the weather undoubtedly dictated the logic of a quick fix.

On

March 19, 1881 a Galesburg newspaper reported that the newly rebuilt depot was

nearly roofed over. Once again the depot became an area for social release.

By

1883, a new grand brick depot farther north at the site of today’s Amtrak

depot, was well under construction so that when completed in 1884, Galesburg’s

original passenger house, the old little “red depow” was abandoned. Although

the freight depot survived until 1921 and the existing switching yards

functioned until 1906 when the new gravity yard farther south opened, the John

Berrien depot disappeared in obscurity.

Ralph

Budd, President of the Burlington Railroad, (CB&Q) assumed control of the

nation’s railroads under Roosevelt during World War II and for the idea of

combining diesel engine propulsion with the Shotweld Process of stainless steel

that created a new type of train called Zephyr. In 1941, Budd asked the question:

Where was the first Aurora Depot? The report handed to him not only studied

Aurora’s depots but encompassed all the depot from Aurora to Galesburg

including Batavia. In this report was a lithograph of the Galesburg depot found

on a 1861 map of Knox County. Around the edge of this 1861 map were

representations of different prominent structures around Galesburg. Among the

varied buildings was a small lithograph of John Berrien’s Galesburg depot.

Clearly by 1941, no known photograph of the Galesburg structure existed. How do

we explain such an avoidance to such a prominent local structure? Possibly

there was animosity felt by Galesburg to its source of problems at Five Points.

So probably this animosity translated into the lack of photographs of such a

vital structure. Did Galesburg lose photographs of the depot in the fire of the

town’s library in 1958? Time and time again, photographs that did survive of

scenes before 1884 somehow leave out the depot. One city directory from the

early 1880s refers to the little wooden depot as not worthy of Galesburg and

the great CB&Q Railroad.

For

years, there has been a small group of people working to find the needle in a

haystack, somewhere there has to be a photograph of Galesburg’s first depot.

Every known photograph was surveyed and scanned to find its orientation to the

town and to the direction of the depot’s location at Five Points. Time and time

again, the depot of a pre-1884 was just out of the frame, just out of reach.

An early

Knox County photographer was Charles Osgood, a local photographer who collected

and sold photos. One wonders, “Maybe some of Osgood’s glass plates of Galesburg

survived and in that collection, there’s a unrecognized depot photograph.”

These things don’t happen though, so a different approach was taken. Using

funds and supplies donated by Bill Selleck, Gary Granberg, and Irene Franckey,

a miniature recreation was created in scale of Galesburg’s depot, freight house

and switching yard circa 1870. This was done just to get a handle on the

changing landscape of the railroad in Galesburg. Even today, as new information

surfaces, this diorama of the early depot is changing. Recently, retired railroad

conductor Mike Thompson has become involved in creating miniature complex roof

shapes of those original buildings at his woodworking shop.

An early

Knox County photographer was Charles Osgood, a local photographer who collected

and sold photos. One wonders, “Maybe some of Osgood’s glass plates of Galesburg

survived and in that collection, there’s a unrecognized depot photograph.”

These things don’t happen though, so a different approach was taken. Using

funds and supplies donated by Bill Selleck, Gary Granberg, and Irene Franckey,

a miniature recreation was created in scale of Galesburg’s depot, freight house

and switching yard circa 1870. This was done just to get a handle on the

changing landscape of the railroad in Galesburg. Even today, as new information

surfaces, this diorama of the early depot is changing. Recently, retired railroad

conductor Mike Thompson has become involved in creating miniature complex roof

shapes of those original buildings at his woodworking shop.

As

each photograph of Galesburg’s old railroad yard was scrutinized, the

orientation was crucial to understanding the photo. Finally a high quality

photograph was acquired showing two steam locomotives sitting back to back on a

full covered revolving turntable. Something odd was at the right of the photo

so that with scanning of the computer and enhancing digital information, that

odd thing proved to be an early railroad coach. This meant we were looking in

the right direction, literally. By using a variety of computer filters that can

sense obscure digital information, a faint outline appeared between the two

steam locomotives. For the first time in easily 60 some years an actual

photograph of the depot existed if only the roof of that depot. It showed

lightning rods among other things. True, it was not the photo we had hoped for

but this was still better than anything we had before.

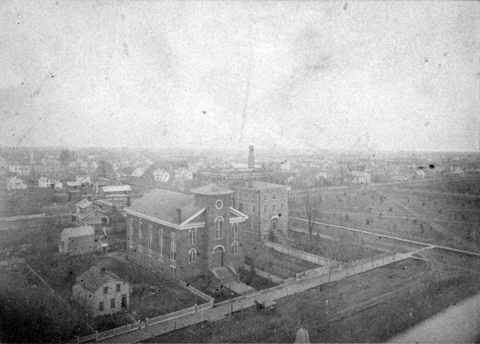

The

earlier one looks back into Galesburg’s past, fewer photographs exist. There

are a handful from the 1860s of which one is a view looking in a southeastward

direction. Unbelievably, the photograph’s view happened to be in the direction

of Five Points in 1866. Carley Robinson of Knox College, helped to obtain a

very, very high resolution scan from the original photograph measuring just

under four inches square yet high in dots per inch. Computers and powerful

programs used in salvaging lost or obscure digital information has been

described as a “black art.” Sometimes different filters in the computer

programs can lead to different conclusions about information obscured in an old

photograph bu slowly the little photo yielded its secrets. There sitting in the

far distance, barely discernible, was Galesburg’s original depot. To its left,

the Q’s erecting shop appeared, devoid of the machine shop that would soon be

built. One of the biggest surprises was the “engine house.” A brief reference,

discovered in microfilm, suggested that an “engine house” may have existed

briefly before the known locomotive roundhouse of 1871. Sure enough, there

appeared a square building instead of a rounded engine house. Maybe the biggest

surprise was that there was a road directly to the front of the depot. Let

there be no mistake, this forgotten road led the way to all arrivals and

departures of early Galesburg.

The

earlier one looks back into Galesburg’s past, fewer photographs exist. There

are a handful from the 1860s of which one is a view looking in a southeastward

direction. Unbelievably, the photograph’s view happened to be in the direction

of Five Points in 1866. Carley Robinson of Knox College, helped to obtain a

very, very high resolution scan from the original photograph measuring just

under four inches square yet high in dots per inch. Computers and powerful

programs used in salvaging lost or obscure digital information has been

described as a “black art.” Sometimes different filters in the computer

programs can lead to different conclusions about information obscured in an old

photograph bu slowly the little photo yielded its secrets. There sitting in the

far distance, barely discernible, was Galesburg’s original depot. To its left,

the Q’s erecting shop appeared, devoid of the machine shop that would soon be

built. One of the biggest surprises was the “engine house.” A brief reference,

discovered in microfilm, suggested that an “engine house” may have existed

briefly before the known locomotive roundhouse of 1871. Sure enough, there

appeared a square building instead of a rounded engine house. Maybe the biggest

surprise was that there was a road directly to the front of the depot. Let

there be no mistake, this forgotten road led the way to all arrivals and

departures of early Galesburg.

9/20/07