BACKTRACKING

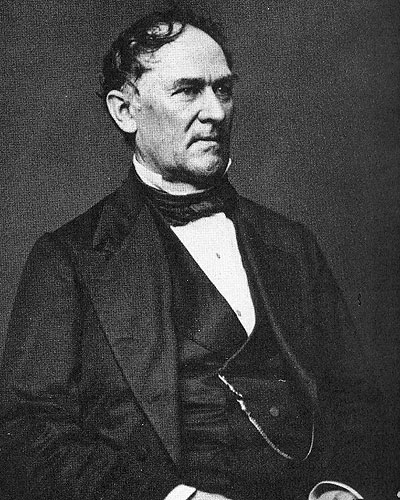

Orville H. Browning

by Terry Hogan

In Lincoln's personal

life, he seemed to know many folks and had a good memory for faces and

names. This was a great help to

him as a local, state and national politician. But he also seemed to have only a few good friends who he

personally confided in and to whom he turned to for trusted advice. One of these few close friends was

Orville H. Browning, of Quincy, Illinois. Browning was to play a significant

role as a friend, an advisor, and an astute politician in Illinois who

significantly helped Lincoln. Despite this, Browning is not particularly

well-known, even in his home state of Illinois. It is not a name you hear around Galesburg's history,

although he had ties here. You

probably don't hear his name in Monmouth's history, but he practiced law there

from time to time. Presumably,

being the insightful reader that you are, you have figured out that I'm

referring to Orville Hickman Browning.

The article title was probably at least a little helpful.

I believe Lincoln first

met Browning during the locally famous Black Hawk War (Duff, 1960; Donald,

1995), although it has also been reported that the two did not meet until 1836

when they were both elected to the state legislature (Hallwas, 1983). Both Lincoln and Browning had enlisted

to serve to help deal with the alleged threat of an Indian uprising. At that time, Lincoln was essentially

penniless and becoming a soldier promised a reliable income. It was also later to become a windfall

for Lincoln when he was given two different parcels of land in Iowa for his

military service.

Orville Browning was a

conservative, cautious lawyer from Quincy, Illinois. Lincoln and he became

friends, as well as professional and political associates, after Lincoln became

a lawyer and began dabbling in state politics. Browning played a major role in the development of the

Illinois Whig party and later, in the Illinois Republican party.

But perhaps a few

stories will be a better option than a listing. Some years ago, I wrote an article about Lincoln being a

"no show" at the U.S. Supreme Court. He failed to submit a written argument to the court and he

failed to appear at the court to represent his client concerning a land

ownership case for property in Warren County Illinois. The case, which was lost, in a close

five to four decision, even without Lincoln's appearance, was referred to

Lincoln by Orville Browning.

Lincoln was expected to be in Washington, and being from Illinois and

known to Browning, it seemed to be a logical choice.

Browning had another

tie-in with Warren County in a somewhat famous court case in Monmouth. Browning's client was the Mormon

Prophet Joseph Smith. Stephen

Douglas was the judge. Lincoln was

involved in the case, but did not attend the trial. Browning won

the case and Joseph Smith was not extradited to Missouri.

Browning also had a run

in with Stephen Douglas in the political area. Douglas defeated Browning in the 1844 election, taking

Browning's seat in the Illinois House of Representatives.

Lincoln also represented

Browning in a law suit against the town of Springfield. Browning had suffered an injury due to

a poorly maintained sidewalk.

Although cities were generally immune from suits, Lincoln successfully

argued that Springfield had an acknowledged responsibility to maintain it and

failed to. Lincoln won the case

for Browning.

In 1839, Lincoln and

Browning were two of the four Whigs who participated in a debate against four

Illinois Democrats. Among the

Democratic representatives was none other than the well-known Stephen

Douglas. Lincoln and Douglas would

later debate again in Illinois in the nationally- followed debates for the

Illinois Senate seat.

In 1856, Browning worked

to build a consensus for the Illinois Republican platform that both the old

Whig party members and the more liberal Republican members could support. He

did so at Lincoln’s request. The platform was adopted by the Illinois

Republicans in Bloomington on May 29.

On June 16, 1856, Lincoln was nominated as the Republican candidate for

the U.S. Senate, with a united organization, based on Browning's consensus

platform.

This set up the great

debates between Lincoln and Douglas, one of which was held in Galesburg at the

Old Main of Knox College. (As an aside, Old Main is the only original site of

the five debate locations that still stands.) Although Lincoln lost the election for the U. S.

Senate, the relatively recent stringing of telegraph lines, allowed the entire

nation to read, nearly verbatim, the debate of the issues. Lincoln lost the election, but through

these debates, he became a national figure. The debates gave him the necessary

national exposure for the 1860 presidential nominee for the Republican Party.

Browning was a trustee

of Knox College. In that role, he

presumably played a major role in convincing Knox College to award Lincoln the

first honorary degree given by Knox. In announcing the degree to the largely

self-educated Lincoln, Browning advised “…consider yourself a ‘scholar’, as

well as a ‘gentleman’ and deport yourself accordingly.” (Knox College, 2005).

For the Republican

National Convention, held in Chicago, Lincoln was able to pick all four of the

"at large" Republican delegates. Orville Browning was one of the four selected by

Lincoln. The key function of the

Convention was to nominate a Republican candidate for the President of the

United States. Orville Browning is

attributed as playing a major role in Lincoln's ultimate nomination by

converting Edward Bates’ (Missouri) supporters to Lincoln supporters when it

became clear that Bates would not be successful.

Frank (1961), who wrote

a book about Lincoln as a lawyer, attributed the associations that Lincoln made

while traveling on Illinois' 8th Circuit Court as critical for his political

success: "The friendships

formed there [Circuit

Court] gave Lincoln the backing which made him a state leader in

Illinois. David Davis was the

manager of his campaign in Chicago.

Leonard Swett, Browning, and many others of the Eight Circuit bar made

up his strength."

As we know, Lincoln was

elected as President and took the office in 1860. After Lincoln was elected,

but before he left Springfield for Washington, Lincoln and Browning met in

Springfield. Browning wrote in his

diary "Lincoln bears his honors meekly. As soon as

other company had retired after I went in, he fell into his old habit of

telling amusing stories, and we had a free and easy talk of an hour or

two."

(Hallwas, 1983).

Lincoln asked Browning

to go to Washington with him, but Browning answered that he could not. But he did travel by train with Lincoln

as far as Indianapolis. During

that trip, Lincoln gave Browning a draft copy of his inaugural speech for

review and comment. Browning

suggested that draft language that spoke of the reclaiming of federal forts

taken by Confederates be deleted from the text. Browning felt the reference

might be too inflammatory. Lincoln concurred with Browning's suggestion and

deleted the reference.

In 1862, Browning was on

Lincoln’s “short list" for nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court. But based

on the pleadings of another Lincoln friend, Leonard Swett, Lincoln was talked

into paying old political debts, and the position was given to David Davis. Davis had played a key role on

Lincoln's nomination and, like Browning, had been part of the 8th Illinois

Circuit Court group of lawyers, including Lincoln, Swett, and Browning (Frank,

1961). This decision may have been

hard for Lincoln to make, as Browning had written to Lincoln, himself, on or

about April 9, 1861, only five days after the Supreme Court position opened on

April 4, after the death of Judge McLean.

Browning wrote to

Lincoln:

It is not

without a great deal of

embarrassment and hesitation that I have determined upon this course, but

having determined upon it, I do not propose to offer any apology for addressing

myself to the task. You know me

about as well as I know myself; and in regards to my fitness for the office, you

know me better - for you occupy a far better stand point for the formation of a

fair and impartial judgment than I do.

If, then, you shall think me competent to the duties of the office, and

shall be at all inclined to gratify me in any thing, I say frankly, and without

any sort of disguise, or affectation, that there is nothing in your power to do

for me which would gratify me so much as this. It is an office peculiarly adapted to my tastes, and

the faithful and honest performance of the duties of which would be my highest

pride and ambition." (Duff, 1960).

Perhaps the decision may

have been made even more difficult by the subsequent receipt of a letter dated

June 8, 1861, from Mrs. Browning, who was also a long-term friend of

Lincoln. She also asked for his

appointment, and noted that she had written the letter "…without his

knowledge when he was attending court in Springfield" (Duff, 1960).

However, Browning did

end up in Washington, and continued to be both an advisor and a listener and

friend to the new President Lincoln. Senator Stephen Douglas died while in

office. The vacant seat was

appointed by the Illinois Governor Yates.

Perhaps through good fortune or perhaps by Lincoln’s encouragement,

Browning was selected to complete Douglas' senatorial term. This gave Lincoln

both extra support in the Senate, and a confidential and trusted ear when it

was greatly needed.

Lincoln was greatly

hounded by office seekers who daily invaded the White House. Given the security provided to recent

presidents and the White House, it is hard to imagine the open door policy that

existed in 1860. Browning tried to

convince Lincoln to limit his availability to one and all as Browning could see

that the office and the public demands were wearing Lincoln down. Lincoln would not heed Browning's advice,

although he was helpful by providing friendship and non-demanding companionship

reminiscent of easier times in Illinois.

The importance of the

Browning- President Lincoln friendship can be shown in two examples- one on

personal tragedy, and the other on civil war strategy. When the Lincoln's son, William, died,

Lincoln asked Orville Browning and his wife, Ekiza, to move into the White

House for a short period of time (Hallwas, 1983). Orville took care of making the funeral arrangements, and

his wife helped take care of Mrs. Lincoln.

Browning is attributed

as being the author of the strategy to attempt to re-supply Fort Sumter. This re-supply effort caused the South

to fire the first shots, thereby initiating the war and painting the

Confederacy as the aggressor. According to Browning's suggestion to Lincoln, it

was important for the northern states to have had the South be the aggressor

(Donald, 1995). As the Civil War

progressed, and emancipation and status of the slaves moved more to the

forefront in politics and in the anticipated reconstruction of the South,

Lincoln needed every bit of glue possible to hold the northern states

together. Death, destruction, the

draft, taxes, and the failure to achieve a quick victory over the South caused serious

erosion in the support of the war in many parts of the North.

The frankness of

Lincoln's and Browning's discussions although undoubtedly helpful for Lincoln

to form and evaluate his public positions, also strained the personal

relationship of these two friends.

In 1861, General Fremont (a Union general), acting on his own,

proclaimed that all slaves belonging to people in his territory who took up

arms against the United States were free.

At this stage of the war, although the proclamation was warmly received

by abolitionists, many voters and many soldiers, were not willing to continue

fighting a war that appeared to have become a slavery issue. Lincoln was forced to issue an order,

modifying the proclamation after Fremont refused to do it.

Browning wrote a letter

to Lincoln concerning Lincoln's reversal of the Fremont proclamation. Lincoln wrote a "private and

confidential"

letter to Browning on September 22, 1861.

It is obvious that Lincoln took Browning's criticism personally by the

tone of the first paragraph of the letter: "Yours of the 17th is just

received; and coming from you, I confess it astonishes me. That you should object to my adhering

to a law which you had assisted in making and presenting to me less than a

month before is odd enough. But this is a very small part. General Fremont's proclamation as to

confiscation of property and the liberation of slaves is purely political and

not within the range of military law or necessity."

Later, in the same

letter, Lincoln chided Browning: "…if you will give up your

restlessness for new positions, and back

me manfully on the grounds upon which you and other kind friends gave me

the election and approved in my public documents, we shall go through triumphantly."

(Letter from Lincoln to

Browning, dated September 22, 1861, published in Stern, 1940, pages 680-681)

In fact, the

emancipation issue became a dividing issue between Browning and Lincoln and

caused an irreparable harm to their friendship, but this time, each man had

reversed their position from the earlier Fremont proclamation disagreement. While Browning and Lincoln remained

friends, the divisiveness of these issues were to effectively eliminate

Browning's role as a personal advisor and sounding board for Lincoln. Browning

argued against abolition of slavery. He felt that his friend, Lincoln, had

fallen under the control of abolitionists and that endangered the support of

the northern populace for the war.

Browning wrote in his personal diary on January 30, 1863, "The

counsels of myself and those who sympathize with me are no longer heeded. I am

despondent, and have but little hope left for the Republic." (Hallwas, 1983).

Browning, at the end of

the Senatorial term that he filled, returned to Quincy and turned once again to

his law practice. In that

capacity, he still remained friends with Lincoln and often used that friendship

to "open doors" for his clients, not unlike current-day

lobbyists. In fact, Browning was

in Washington and visited Lincoln at the White House on April 14, 1865, the day

Lincoln was shot at Ford's Theater.

After Lincoln's death,

Browning was to once again serve in the national government. Browning was the

Secretary of the Interior (1866-1869) in the Johnson administration. He also served as the Attorney General

in 1868.

In 1869, Browning

returned to Quincy and took up his law practice for the last time. His law partner from 1837 to 1873 was

Nehemiah Bushnell. Bushnell had

been the president of the Northern Cross Railroad. The town of Bushnell (Illinois) was named for him.

Browning died on August

10, 1881. He had served Lincoln

well as a good friend, an advisor, and a supporter during those frequent moods

of depression that Lincoln was noted for.

It is unfortunate that his frankness concerning the fundamental

difference of slavery tainted the exercise of his role in the remaining time of

Lincoln's term.

Browning was one of

Illinois' own.

References:

Donald, David. 1995. Lincoln. Simon & Schuster.

New York.

Duff, John. 1961. A.

Lincoln, Prairie Lawyer. Bramhall House. New York

Frank, John. 1961.

Lincoln as a Lawyer.

University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

Hallwas, John. 1983. Western

Illinois Heritage.

Illinois Heritage Press. Macomb, IL

Knox College. May 2005. Commencement

2005.

http://www.knox.edu/x9684.xml

Stern, Philip. 1940. The

Life and Writings of Abraham Lincoln.

The Modern Library. New York.

The Lincoln Institute.

2005. Orville H. Browning (1806-1881). “Mr. Lincoln and Friends”

website. www.mrlincolnandfriends.org

The Lincoln Institute.

2005. Mr. Lincoln’s White House.

http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org