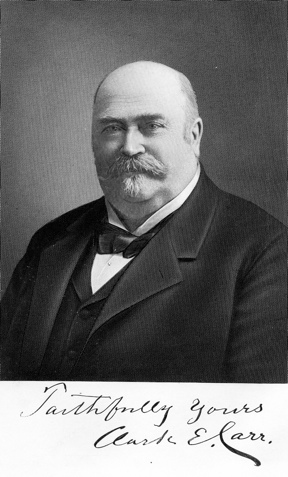

Clark E. Carr: A Galesburger among royalty

By Lynn McKeown

Clark E. Carr was a big man

in town (in more ways than one) in the Galesburg of a century ago. He was a

lawyer, businessman, Galesburg postmaster, sometime newspaper editor, orator

and local Republican Party bigwig, and involved in many other local

organizations. The "most roly-poly fat man in town," as Carl Sandburg

called him, was also a Shakespeare enthusiast and fairly good writer, who late

in life published a number of books.

Carr's books include a

memoir called My Day and Generation, published in 1908. In another article I described

the western trip recounted by Carr in the opening, long chapter of this memoir.

It was a memorable trip, with Carr as a young man accompanying former Illinois

Governor Richard Yates and several other important men of the time on a trip

over the newly completely railway line to California. Highlights of that trip

included a visit to Brigham Young and the Mormon colony in Utah and a practical

joke played on Carr by Yates, who persuaded young Carr to take what turned out

to be a hair-raising ride on the cowcatcher of the locomotive as they descended

out of the mountains into Salt Lake City.

Other chapters in the book

included Carr's experiences with noted men and events of his time, including a

visit to the White House and an appearance by a disheveled Lincoln suffering

from the flu. (Stories about such notables as Lincoln, Douglas and Grant are

worked into the background of CarrŐs historical novel The Illini.) And some of the more

interesting chapters in My Day and Generation are about CarrŐs

improbable experiences with European royalty.

Carr apparently had

aspirations for a distinguished political career. He tried unsuccessfully to

get the Republican nomination for Illinois governor and was a popular orator at

public functions. Finally, in 1889, he was rewarded for his labors for the

Grand Old Party by being appointed by President Benjamin Harrison as minister

plenipotentiary (ambassador) to Denmark, where he served until 1893. Carr

describes many of his experiences while in this position in his memoir, often

with a dry, self-deprecating sense of humor that may have come from his

family's New England background.

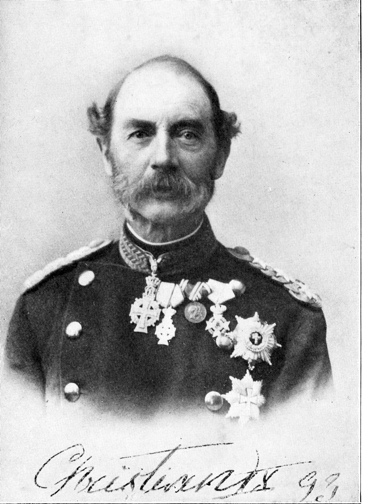

Carr's first official visit

to King Christian IX went well. He didn't know what to expect when he, an

American "from the Illinois prairie," encountered Danish royalty, but

the king proved to be an affable old gentleman who spoke perfect English, and

Carr also soon made friends with Crown Prince Frederick, a friendship which

seems to have lasted even when Carr later returned to Galesburg, when the two

corresponded. A social event that soon followed, however, proved potentially

embarrassing to the newcomer from Illinois.

Carr's first official visit

to King Christian IX went well. He didn't know what to expect when he, an

American "from the Illinois prairie," encountered Danish royalty, but

the king proved to be an affable old gentleman who spoke perfect English, and

Carr also soon made friends with Crown Prince Frederick, a friendship which

seems to have lasted even when Carr later returned to Galesburg, when the two

corresponded. A social event that soon followed, however, proved potentially

embarrassing to the newcomer from Illinois.

Carr was invited to a royal

social gathering at the castle – a gathering that would include visiting

relatives from other countries – and since the king's children had

married into several other royal families, he would be surrounded by royalty,

including the Czar of Russia and the King of Greece, as well as the Danish

royal family. One of King Christian's sons had been installed as King of Greece

by the ŇGreat Powers,Ó and two daughters had married into the royal families of

Britain and Russia. They were all present, along with other princes and

panjandrums. (The king later told Carr, jokingly, that he and the queen were

"the grandfather and grandmother of Europe.")

Carr was invited to a royal

social gathering at the castle – a gathering that would include visiting

relatives from other countries – and since the king's children had

married into several other royal families, he would be surrounded by royalty,

including the Czar of Russia and the King of Greece, as well as the Danish

royal family. One of King Christian's sons had been installed as King of Greece

by the ŇGreat Powers,Ó and two daughters had married into the royal families of

Britain and Russia. They were all present, along with other princes and

panjandrums. (The king later told Carr, jokingly, that he and the queen were

"the grandfather and grandmother of Europe.")

Carr had been told that one

must never turn one's back on royalty. How was the small-town American Carr to

deal with this problem of royal etiquette? "What was I to do with my

back?"

as he exclaims in his memoirs. As it turned out, the Danish royal family was

notable for its informality and unstuffiness, Carr survived the ordeal with no

faux pas, and the Crown Prince laughed when Carr later told him of his supposed

predicament.

Carr had an especially

high, rather chivalric, regard for Queen Louise. Once, when on a trip to

southern Europe, he visited the island of Corfu, where there was an estate

belonging to her son, the King of Greece, and attempted to obtain a present for

her. The estate included an orchard, and Carr decided some of the fruit would

make a nice present for the Queen when he got back to Denmark. The gardener he

talked to was skeptical of what may have sounded like an improbable story, but

he finally obtained a basket of Mandarin oranges, which Mrs. Carr later

presented to the Queen. Maybe the Greek gardener just considered him another

one of those crazy Americans.

There's very little in

Carr's memoir about his official duties, possibly because there really wasn't

much to tell, since it was a peaceful time and American relations with the

small country of Denmark were friendly. On one occasion, however, the Queen had

a complaint.

On one of his visits to the

palace, the Queen took him to task. It seems that Danish women were getting

poor prices for their cabbages when they were shipped to New York because of a

recent tariff sponsored by "that horrid McKinley," as the Queen

called the Ohioan, then a U.S. Congressman. She hoped the ambassador could do

something about it. He told her he would try, and he passed along the complaint

to the U.S. government, though he knew nothing would come of it.

Carr seems to have been

very impressed with the Danish royal family, even though this was a time when

monarchs throughout western Europe were losing power and being reduced to

ceremonial roles. This royal family does seem to have had more intelligence and

character than some, however. (They were the subject of an interesting

documentary that appeared recently on PBS.) Perhaps the character and integrity

of the family was shown in an incident that occurred at a later time.

During World War II,

Christian X, who would have been a young man when Carr was attending social

functions and drinking champagne at the Danish court, was King of Denmark. He

seems to have been popular, often going for horseback rides on the streets of

Copenhagen. He looked the part of a Scandinavian king and showed some character

when the Nazi army rolled into Denmark. There wasn't much he or any of the

Danes could do as their small country was occupied. But when Jewish citizens

were ordered to wear a Star of David on their clothing, King Christian showed

his solidarity with them (and perhaps contempt for the Nazis) by also appearing

in public with a Star of David pinned to his coat, though he was not, of

course, Jewish. The king riding his horse through Copenhagen streets became in

many ways a "national symbol," and eventually, after the resistance

began to be more active, the Nazis confined the royal rider to his castle.

Carr's service in Denmark

ended when a Democrat, Grover Cleveland, became President in 1893. The rotund

Republican gentleman returned to his home on Prairie Street in Galesburg where

he lived the rest of his days, a popular speaker and writer, telling humorous

stories of his adventures around the U.S. and, during one four-year stretch,

among European royalty.

My Day and Generation is

available at local libraries, and quite nice copies at a reasonable price are

available from used book dealers on the Internet at such sites as abebooks.com

. Carr's writing style is rather formal and dry, but if you can adjust to that

and have an interest in history, his books are entertaining.

12/13/07